The Beginning of the Age of Intolerance

When I studied the history of early modern Europe, one of the core topics in my readings was the development of modern religious tolerance and pluralism. To stuff a massive, far-reaching subject into just one question: how exactly did Western societies, in only the span of three hundred years, go from burning people alive who just disagreed with ideas like the doctrine of the Christian Trinity to letting atheists and other non-Christians publish books and discuss their views in public?

There are numerous interlocking factors historians of the period tend to agree on as at least part of the answer to the question of how the Age of Intolerance ended and the current Age of Pluralism in the West came to be: increasing literacy and the spread of published books that made censorship more difficult to manage and even impractical in some places; the uneven but growing prosperity and living standards in western and central Europe; the decline of violence in the early modern era which also fueled campaigns against public executions and even the death penalty as a whole; the fact the Reformation and the myriad Protestant denominations it spawned eventually made the prospect of enforcing any kind of orthodoxy on people impossible in practice; and so on. You could easily fill a library with books addressing such topics.

The question I don’t see discussed as often is how intolerance became the status quo in Europe for so long in the first place. Now I’m not an expert in ancient history (and I worry that, when they finish reading this essay, actual historians of antiquity will remember this bit and roll their eyes), but the subject became something of an obsession for me as I was doing research for my current book project, a history of despair. After all, the rise of intolerance was likely a tremendous source of despair for those living in late antiquity, and the topic proved to be a more nuanced and daunting one than I expected.

First, though, a big caveat: when we talk about tolerance giving way to intolerance in the ancient Mediterranean and Middle East, we’re not actually talking about “religious tolerance” or “freedom of conscience” in the modern sense. If anyone in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern antiquity ever conceived of the idea of some innate, absolute right to one’s beliefs (or non-belief) and practice, it apparently wasn’t something those in power ever took into consideration. Of course, this makes sense when you consider how most of the world still practiced polytheism with gods constantly crossing national boundaries, pantheons mixing with each other or changing according to region, and gods of foreign peoples being equated with each other. In such a world, religious orthodoxies aren’t just impractical, but practically incomprehensible. For example, even with Christianity’s claims of being the exclusive truth, that didn’t stop the third century Roman emperor Alexander Severus from reportedly worshipping Jesus Christ alongside the mythological hero and religious visionary Orpheus and the philosopher-mystic Apollonius of Tyre.

To be sure, though, it was taken for granted that monarchs and republics alike had a right to ban any cults deemed to be morally or politically subversive, and foreign cults seeking to make inroads into a new country were sometimes treated with suspicion if not outright hostility. Legends hold that the god Dionysus and the goddess Cybele were both met with violent opposition in Greece in the legendary distant past, efforts at persecution which were always naturally punished by the divine with plague or ecstatic madness. It’s unclear what if any hazy historical memories such myths might preserve, especially when such stories are more concerned about glorifying the deity whose worship mortals once dared to suppress.

In the second century BCE, the Senate of Rome acted against the cult of Dionysus’ Italian counterpart Bacchus on the pretext that the cult’s activities had become morally and even politically damaging (it didn’t help that the cult had a large following of upper-class Roman women, which the Senate made sure to complain about). Even then, the cult of Bacchus wasn’t outlawed, but rather was placed under state control and became heavily regulated. The Maccabean Revolt of the second century BCE, a Jewish revolt against the Seleucid Empire ending with the establishment of a new Jewish kingdom, was a response to a harsh ban on Jewish practices, but the original causes had much to do with internal politics in Jerusalem and the Seleucids’ conflict with the Ptolemies of Egypt rather than an initial antipathy toward the Jewish religion. Also, the Maccabean Revolt was arguably as much a civil war between hardline Jews and Jews who accepted Hellenistic influences as it was a revolt against an occupying power. Then, following the conquests of Gaul and Britannia, a series of edicts under the Roman emperors banned the Druids, the priestly caste of the Celts. The excuse was that the Druids indulged in the taboo practice of human sacrifice, but likely the real reason was that they were supporting resistance movements.

There are a few possible hints, too, of the suppression of non-belief, but these are also shrouded by ambiguity and politics. The most famous case by far is Socrates’ trial and execution for impiety in Athens, although both ancient and modern commentators agree the real motive behind Socrates' trial was Athens’ fragile democracy doing what it could to stifle subversive opinions. Similarly, the fifth century BCE philosopher Anaxagoras was exiled from Athens for impiety, but it might have really been over his politics. The poet Diagoras, whom many writers in antiquity suggest was an atheist, probably was persecuted and forced to flee Athens because of his beliefs, although it certainly didn’t help that Diagoras publicly divulged and ridiculed the sacred secrets of the Eleusian Mysteries. Even with such cases, the works of philosophers whose ideas held that the world was created through natural rather than divine forces or who, like Euhemerus, argued that the gods were just prehistorical great figures who became divinized over time were accepted and even celebrated. As for ancient societies outside ancient Greece, like Mesopotamia and Egypt, there are only debatable scraps in the surviving literature that suggest a skepticism about the existence of the gods, but there are also no accounts I know about of people being persecuted or killed for their non-belief, at least no such stories that survive.

While in a modern light instances like the persecution of the Druids and the trial of Socrates still do qualify as examples of religious persecution, they are the exceptions that tend to prove the pluralistic rule. The same could be said for early Zoroastrianism. Religious scholars can debate over whether or not Zoroastrianism actually was the world’s first monotheistic religion, as its current adherents view it, but it was nonetheless unique for having a definitive canon of scripture and concepts of false gods and a judgment day. Even though the religion literally demonized certain gods, the evidence that the Achaemenid Empire of Persia ever tried to suppress any cult in Zoroaster’s name only comes from ambiguous, unclear references, and the argument once cited by modern historians that the Persians were hostile to the Egyptian native religion has been debunked. On the contrary, the Achaemenid Empire was rather famous for defending what we might today call religious freedom. The account justifying the Persian invasion of Babylon held that its king Nabonidus had deliberately neglected the worship of the city’s patron god Marduk, and Shah Cyrus “the Great” made his name in the Hebrew Bible by restoring the First Temple of Jerusalem. No doubt all this was for the purposes of propaganda, but beneath the imperial messaging had to be a pillar of truth that the Persians not only allowed the myriad peoples under their rule to worship freely, but they would at least occasionally sponsor and restore traditional practices when they were endangered.

Still, the giant crucifix in the room is Christianity, easily the most notorious case of ancient intolerance. While certainly the Romans’ treatment of Christians would never fit into any modern ideal of a pluralistic society, the Romans’ reasons were more complicated than simply Christians being seen as spiritually wrong. The Christian refusal to worship the emperor bordered on outright sedition, and, unlike the Jews whose beliefs could at least claim some kind of ancient authority, the Christians were seen by the Roman elites as, in the words of the first century CE Roman historian Tacitus, a newly formed “mischievous superstition.” Further, a few historians of early Christianity like Candida Moss have argued that earliest accounts of mass persecution, like the proverbial one under the Emperor Nero, were exaggerated, if they happened at all. Even accounts left by Christian sources illustrate Roman officials acting more like exasperated bureaucrats than fanatical persecutors. Martyrdom stories often portray Romans as trying to give their would-be victims a way out from execution. This impression is supported by non-Christian sources as well. The Emperor Trajan instructed Pliny the Younger, who was at the time a provincial governor in modern-day Turkey, to bring any Christians to trial, but to also not seek them out and to never use anonymous accusations as evidence. What mass persecutions of Christians did happen under the emperors of Rome actually took place during the Age of Intolerance itself, which I would argue began before the Christianization of the Roman Empire.

So, in sum, antiquity could be described as pluralistic, just not in a modern sense. There was no concept as far as we know of a universal and innate right to follow or preach one’s conscience, but governments tended to extend a certain kind of respect for gods and cults that could invoke their own staying power and ancient legitimacy. When religions were persecuted, it was for reasons that were largely political and social but rarely doctrinal, or at least not until the initial wave of persecution would encourage dehumanization of the persecuted. It seems overall, in a world where even the Romans felt obliged to offer all possible courtesies to the gods of the peoples they conquered, there was no reason to risk getting on a god’s bad side by needlessly killing their followers.

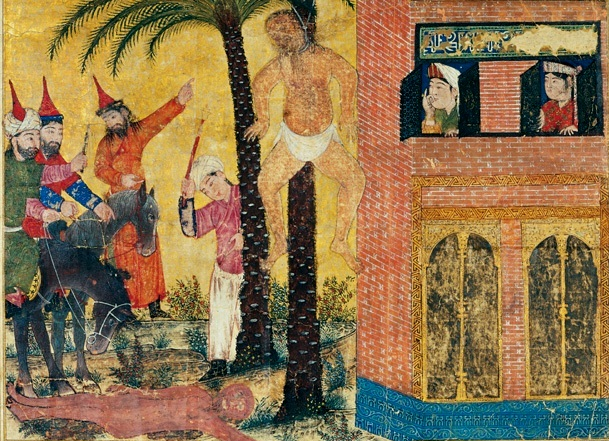

In broad strokes, this was the status quo, until about the third century CE when the two superpowers of the region, the Roman and Persian empires, almost simultaneously started approaching their religious policies in ways that had no real precedent, outside perhaps the persecution of the Jews under the Seleucids (and even that, I would argue, at least had its origins in war, politics, and cultural and social tensions). By 224 CE, a new Zoroastrian imperial power based in Persia under the Sassanid dynasty emerged. At first, the Sassanid shahs followed in the traditional practice of open tolerance. Then, starting in 271 when Bahram I ascended to the throne, the Sassanids would engage in sporadic persecutions of Jews, Christians, and Manichaeans. The founder of Manichaeism, the prophet Mani, was even martyred under Bahram I.

At roughly the same time by the second half of the third century, in the Roman Empire the persecution of Christians became more widespread and constant, first under the Emperor Decius and then reaching a crescendo with the Emperor Diocletian, quite possibly the most authoritarian and micromanaging emperor the Roman Empire would ever have. After Emperor Constantine I made Christianity the state religion of the empire, Christians would not only employ the power of the state against pagans and Jews, they would also go after the wrong kinds of Christians. By 385, just about 72 years after Constantine legalized Christianity, the Bishop Priscillian earned the dubious distinction of being the first Christian to be executed for heresy at the order of Christian authorities. Unlike earlier attempts by governments against certain religions or cults, these persecutions had no obvious political or social motive at any point; on the contrary, they tended to create political and civic problems.

So…what changed?

This is where I might be exposing my lack of expertise, but I think there is a case to be made that something about the way people understood what we would call religion changed. It wasn’t just the rise of Christianity which condemned all other faiths as false, but a fundamental, seismic shift in what people came to need and expect from their religions, whether it was the cult of Mithraism in the Roman Empire or the reformed Zoroastrianism of the Sassanids. At least from the Mediterranean and European perspective, from a world composed mainly of city-states and small kingdoms and tribal territories, Alexander the Great and then the Romans forced together from these disparate pieces a cosmopolitan world of diverse cultures and societies tied together through a common language and several governments (under the Hellenistic kingdoms that rose in Alexander the Great’s wake) or later the Roman Empire. Something about this new world made people look for more than the old state-run civic cults. Just as competing philosophical schools like the Neoplatonists and the Stoics promised personal happiness to anyone who truly understood and lived their teachings, the mystery cults of Orpheus, Isis, and Mathias along with Christianity and Manichaeism offered adherents myths that could make sense of a brutal and unfair existence, a truly personal relationship with the divine, and a good afterlife. The mystery cults were admittedly not new. The cult of Orpheus, in fact, had a long history stretching back past the written Greek language into prehistory, and the gods Isis and Mithra had similarly primordial pedigrees in their native lands of Egypt and Iran respectively. Still, empire and the emergence of Greek and Latin as lingua francas facilitated their spread from the Middle East to the Atlantic Ocean. Given the greater dearth of evidence, it's harder to speak to the Persian perspective in this era. Perhaps, though, these changes affected them as well, since Iran as a former conquest of Alexander the Great was also touched by Hellenism.

There’s a risk in oversimplifying this story. Many people across the Roman Empire also converted to Judaism, which fed from the same cultural stew but remained quite distinct from the mystery religions, or they still found a sincere emotional and personal satisfaction from the traditional gods and rituals and the philosophical schools as well. Even so, it’s fair to claim that the better-off people who lived in this wealthy, interconnected, urban, and (mostly) peaceful world of the Roman Empire at its height had the time and the leisure to find ways to fill a void their own communities’ traditional gods could not. It was the same impulse and the same luxury of time and contemplation that had motivated people to shop around between Stoicism, Neoplatonism, Cynicism, and Judaism. The nature of the Roman Empire made it possible for even someone just in the mercantile class who lived in small-town Italy to find spiritual comfort with a goddess from far-off Egypt who would not have been known to even the elites from prior centuries. That’s exactly what happens in the Roman novel The Golden Ass. The protagonist frees himself from the curse that turned him into a donkey by converting to the cult of Isis and receives a vision from the goddess herself, who tells him, “I am here in pity for your misfortunes, I am here as friend and helper. Weep no more, end your lamentations. Banish sorrow. With my aid, your day of salvation is at hand.” All this is to say that religion became even more of a personal affair, with more people becoming dedicated to religions from outside their home regions that offered a compelling narrative about life under metaphysical forces of good and evil (like Manichaeism) or demanded faith that strictly excluded any other gods (like Judaism and Christianity). Likewise, religion takes on a new significance when it becomes a matter of cosmic truth and personal salvation, and not just one of personal taste, of your occupation, or who the patron gods of your people and your hometown are.

Ironically, another cause is the very forces that began the destruction of this cosmopolitan state of affairs. Historians debate over the causes, but the entire Eurasian continent was hit by crises in the third century, with China’s Han dynasty collapsing, the Parthian Empire succumbing to the Sassanids in Iran, and the Roman Empire nearly coming to an end because of decades of civil war and a dizzying number of emperors dying in not so mysterious incidents. The Roman Empire would survive, but this “Crisis of the Third Century” changed the empire forever. Except in the wealthier cities of the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa, funds that used to go toward funding civic life in the cities were instead diverted toward a larger army, with the result that traditional festivals and the construction of new public buildings virtually stopped. The Roman Empire that survived the crisis was still rich and powerful, but it was a deeply changed institution. The emperors were always practically absolute monarchs, but by the end of the crisis they dropped all the old republican pretense of just being executive statesmen and became divinely ordained monarchs who deserved gestures of respect once reserved only for statues of the gods. Along with this upgrade in prestige, the emperors were also at the top of a government that had been centralized and expanded since the days of Trajan and Pliny the Elder, designed to cater to a larger army and a vaster bureaucracy. It was this transfigured empire that would launch the most brutal persecutions of Christians. Certainly it wasn’t a coincidence that the bloodiest campaign of persecution of Christians was carried out under Diocletian, the emperor most responsible for engineering the new imperial style. Nor did Diocletian have a place in his new order for Manichaeans. They were reportedly burned alongside their holy books. With Christianity becoming Rome’s state religion after the conversion of Constantine I, the power of the Roman state would be turned against Jews, Samaritans, and those deemed Christian heretics.

At practically the same time, the Sassanid Empire that emerged in Iran made Zoroastrianism the source of its political legitimacy. To that end, it organized and sponsored the religion to a degree the previous Achaemenid and Parthian rulers did not, to the point that a Zoroastrian ecclesiastical hierarchy was set in stone and a clear, definitive orthodoxy began to be enforced. There were still high-ranking Jewish and Christian members of the Sassanid aristocracy and military. In 410, Shah Yazdegerd I even hosted a Christian synod and allowed a Christian church patriarchate to be founded in the capital of Ctesiphon. Nonetheless, although the persecutions in Iran are less documented and understood by modern historians than the persecutions that took place in the Roman Empire in late antiquity, waves of persecutions against Jews and Christians would continue throughout Sassanid history, with their main targets apparently being upper-class Zoroastrian apostates. Historians of the Sassanid Empire like Aptin Khanbaghi and Richard E. Payne do suggest such persecutions may have been partially political in their motivation, given the rank of most of the persecuted and especially since the association between Christianity and the Sassanid Empire’s greatest rival, the Roman Empire, and the sometimes hostile neighboring kingdom of Armenia made Christianity a fifth column within the empire. Still, the reality of persecution and the fact that Zoroastrianism had become a tightly organized religion that bequeathed a great deal of legitimacy to the state, much like the role Christianity came to play within the Roman Empire, is too strong a similarity to dismiss.

The voices that have been preserved from this time do reveal a spiritual hostility, one justified by faith and the needs of the religion alone. Augustine of Hippo articulated a case for religious coercion, comparing imposing one’s beliefs on someone unwilling to forcing a sick patient to accept medical treatment. Augustine and others were completely heedless, to say the least, of arguments that such coercion would only undermine civic order. While Zoroastrian writings are sadly lacking, especially compared to the wealth of literature coming out of early Christianity, we do have an inscription at the ancient site, the Cube of Zoroaster, in the province of Fars. It was left by Kartir, the high priest who likely orchestrated the trial and execution of the prophet Mani. In it, Kartir boasts of “striking down” Zoroastrian heretics along with Manichaeans, Christians, Jews, Mandaeans, Hindus, and Buddhists as well as dealing with his fellow priests who were guilty of error. Such a proclamation would have been quite literally inconceivable to Cyrus the Great.

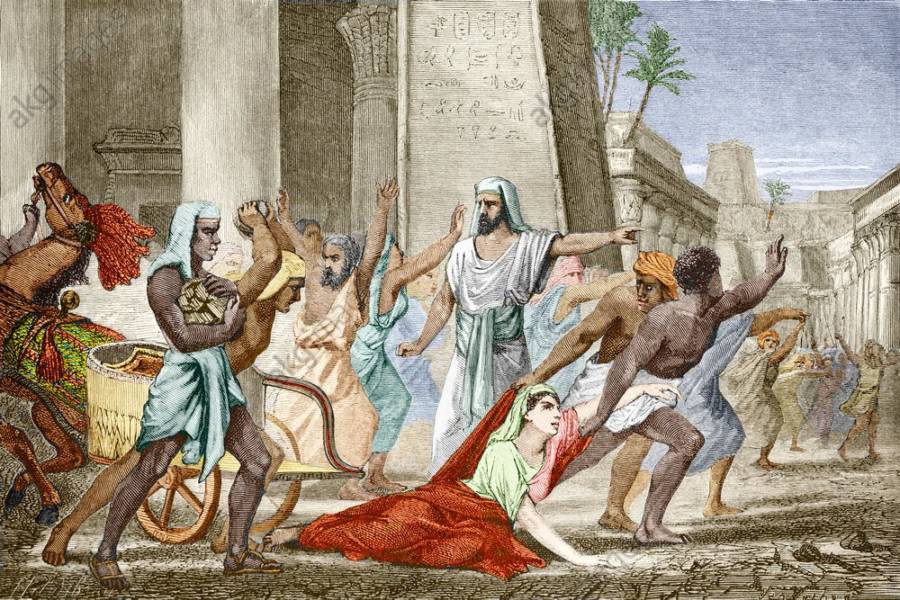

This is largely a history written by the victors and the oppressors like Kartir, but history is not actually written by the victors, at least not always, and a few of the stories of the people who were on the wrong sides in this Age of Intolerance do survive. The philosopher Hypatia’s murder at the hands of a Christian mob in Alexandria has become a legendary example of intolerance versus freethought, but there are others. A pagan historian named Zosimus wrote of the time just a generation or so before his birth when the Roman emperor Theodosius in the early fifth century, encouraged by the fanatically intolerant Ambrose of Milan, practically outlawed polytheism: “The abodes of the gods were assaulted throughout city and countryside, and danger threatened all who believed in deities or who looked to heaven and venerated its phenomena at all.” In seventh-century Rome, a Jewish poet, Solomon the Babylonian, wrote about living under constant pressure to convert and the threat of violence: “They strip us and they scorn us, call us ‘hound’—Each shaveling priest and monk and fool and knave. We hear their taunts—unshaming-shamed, tongue-bound.” Archaeology has revealed that, in the Egyptian city of Menouthis, a secret temple was used for the worship of Egypt’s traditional gods until 484, when Bishop Peter of Alexandria and some monks discovered the temple and smashed the idols inside. As the historian Beátrice Caseau points out, there was no way the secrecy of the temple could have been maintained without the complicity of local Christians, a hint toward just how surprisingly complex the question of tolerance and intolerance was even then.

There were even those who lived through the dawn of the Age of Intolerance, like the philosopher Damascius, who told his story in a manuscript he left behind, The Philosophical History. A native of Syria, Damascius travelled as a student to Alexandria, where he lived almost a century after the murder of Hypatia. There, he was able to study philosophy, rhetoric, and science, but there were danger signs. His brother Julian was beaten by authorities when he was found out to be a pagan and was forced to give up the names of other non-Christians. Despite his own lack of Christian faith, Damascius managed to take a post teaching at the age-old Academy of Athens, founded by Plato in 387 BCE. Then the Academy was shut down by the order of the Emperor Justinian, as part of his crackdown against pagans and other non-Christians. Damascius and other teachers and philosophers fled to the Persian Empire. They could not adapt there—either because of homesickness or because they found intolerance there as well—so eventually, taking advantage of a provision in a peace treaty between the Eastern Roman and Persian Empires that protected them from legal prosecution, they returned. What happened afterward is unknown. In one poignant and chilling passage, Damascius describes seeing the Alexandria he knew, the city of intellectual debate and learning, “being swept away by the torrent.”

What fascinates and depresses me equally is that, looking over what patches of evidence we have, it seems history did not have to go in this direction. There are traces of a potential alternate timeline, which I certainly didn’t expect when I began this research. At the very least, there were people alive when the Age of Intolerance was taking hold who could at least envision another future. In the 360s, to commemorate the Emperor Jovian’s policy of reconciliation between Christians and pagans, one of his ministers Themistius wrote Oration 5. Among other points, Themistus argued that religious toleration brings peace and security to the population, that many different beliefs add to the world’s richness, and that God clearly granted humans free will in matters of belief and faith. While defending (ultimately, in vain) the presence of a statue of the goddess of victory in Rome’s Senate house from Ambrose of Milan, the pagan senator Symmachus wrote poetically about what Christians and pagans have in common: “They gaze at the same stars; they share the same sky, the same world twists around them all. So what does it matter which system each human uses to search for the truth? Such a great mystery could not be reached by one way only.” Pagan philosophers and Christian clergy were sometimes friends and even dedicated their books and treatises to each other.

Whether it was intellectuals laying out the groundwork for a world where pagans and Christians could have coexisted or Egyptian Christians protecting their pagan neighbors from their own clergy, I think there is ample reason to believe the Age of Intolerance was not inevitable. Nor was its success after the fifth century to be total. The signs are there, for those who look: a Jewish courtier serving under a Christian king in sixth-century Gaul (although he was assassinated by a convert); William of Ockham writing theology in the thirteenth century that at least tacitly acknowledged arguments against the existence of God, suggesting such doubts may have still been held by people in his time, even if they dared not express them; the fourteenth-century Byzantine philosopher Gemistos Plethon stewing over (although not openly) the idea of reviving the fortunes of the dying Byzantine Empire by replacing Christianity with a new-old religion that mixed the old Greek gods with Zoroastrianism; and, of course, the countless heretics and non-conformists and freethinkers who were usually silenced but sometimes regardless left behind traces of their existence until the Age of Intolerance gave way to the Age of Pluralism.

But I keep returning to the question: why did the Age of Intolerance get to a point where it became dangerous to be anything other than a certain type of Christian at all? I think the most likely answer is the one I expressed, the reversed mirror image of the reasons why it ended: shrinking literacy rates until only a small clerical class could read and write, the decline (and complete collapse in some areas like Britain) of the city-based civilization that had defined the Mediterranean for centuries, and a rise in violence and instability. Still, I don’t believe material causes are the entire answer, and in any case the causes I mention may not apply equally to the Zoroastrians of the Persian Empire. It is possible that the pressures that brought about Rome's Crisis of the Third Century and the rise of the Sassanids also shaped the form both Zoroastrianism and Christianity took (and, perhaps, also the form polytheism in Rome after the reforms of Diocletian and Julian the Apostate would have taken) as strict institutions intertwined with their respective states. Because the Zoroastrian, late pagan, and Christian experiences were so similar, I do believe there are all part of a profound shift in how many people related to and thought about their gods, even if the seeds of that change already long existed with the ancient mystery cults like Orphism, and the consequences of that change still reverberate.

I’m personally dissatisfied with this answer, though, even if it is my own. It would be easy and strangely comforting if the Age of Intolerance could be seen as just a symptom of a tangible, material decline that may not happen again. As I write this, I am living in the Age of Pluralism, a time not unlike the era before the Age of Intolerance, when someone who was raised Catholic in rural North Carolina can, for the most part, choose between agnosticism or Islam or Wicca and potentially access the knowledge and even possibly the community to help make that choice a reality. But I am reminded that it is also a time when the order of things seems fragile and a catastrophe rivaling or surpassing what overtook the civilization of Mediterranean antiquity—from another global war, climate catastrophe, or simply from the ineptitude and greed of our elites—seems disturbingly possible. Nor is it much of an exaggeration to say there are those with considerable power and a large platform who would like to see the return of something like the Age of Intolerance (a few of them will say so explicitly). All we’re left with is a lesson history often teaches: even in better times, progress should never be taken for granted.

Sources:

Caseau, Béatrice. "Late antique Paganism: adaptation under duress." Late Antique Archaeology 7.1 (2011).

Damascius, The Philosophical History, ed. and trans. Polymia Athanassiadi (Athens: Apamea Cultural Association, 1999).

Drake, Harold A. "Lambs into lions: explaining early Christian intolerance." Past & Present 153.1 (1996).

Lancon, Bertrand. Rome in Late Antiquity: Everyday Life and Urban Change, AD 312-609, trans. Antonia Nevill (New York: Routledge, 2000),

Patterson, Lee E. “Minority Religions in the Sasanian Empire: Suppression, Integration and Relations With Rome” in Sasanian Persia: Between Rome and the Steppes of Eurasia, ed. Eberhard W. Sauer (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017).

Payne, Richard A. A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015).

Roth, Cecil. The History of the Jews of Italy (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1946), 72. [This was the source for the translation of the poem by Solomon the Babylonian].

Zosimus, Historia Nova, trans. James J. Buchanan (San Antonio, TX: Trinity University Press, 1967),