The Art That Made Me: Time and Magik

This is the first of a series, possibly. I really don't know. Something I read reminded me of this game's importance to me, and I would never say no to an excuse to talk about obscure media from the '80s and '90s.

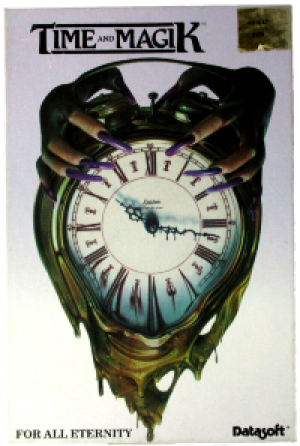

When I was nine years old or thereabouts, my mom offered to buy me something at a flea market, almost certainly as a reward for letting her shop in relative peace. One vendor had a selection of discounted and used computer games. Somehow, one of their offerings was what I would learn much later was a British adventure game titled Time and Magik. I suspect I probably wouldn't have been interested had the game been packaged with its original box cover:

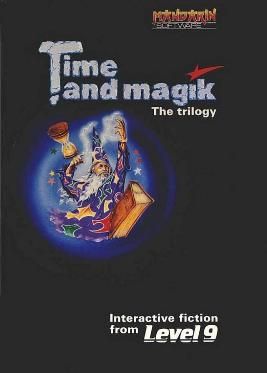

Instead, this was the cover that enticed me:

How could I resist a cover so metal? Thus began the story of how a text-based adventure game written by a British housewife and programmed and distributed by a British company shaped the life of a boy in the United States.

There isn't much out there about Time and Magik, even in the retro gamer corners of the Internet. This is despite the fact that, in the wild frontier days of computer games, its publisher Level 9 was one of the big names among early adventure game fans along with Infocom/Legend Entertainment, Lucasfilm, and Sierra. Adding to its obscurity is that Time and Magik both is and isn't the game I'm actually talking about. In truth, I'm just talking about Lords of Time, originally released in 1984, but four years later it was wielded together with two other unrelated games to make a "trilogy" that was bundled together in the form of Time and Magik, which is largely how the game is known today. The box I got even came with a novella meant to bind the games together. It was an epic about timeless beings forced into a reality bounded by time, a kingdom that is the last refuge of magic (sorry, magik), and a mad, corrupted wizard. However, originally Lords of Time was just about the nine Timelords who were changing history for reasons unexplained, other than they were just evil. Since it was 1984, the manual pretty strongly hints that President Reagan's election was one result of the Timelords' sinister meddling. How else could a b-movie actor become President of the United States?

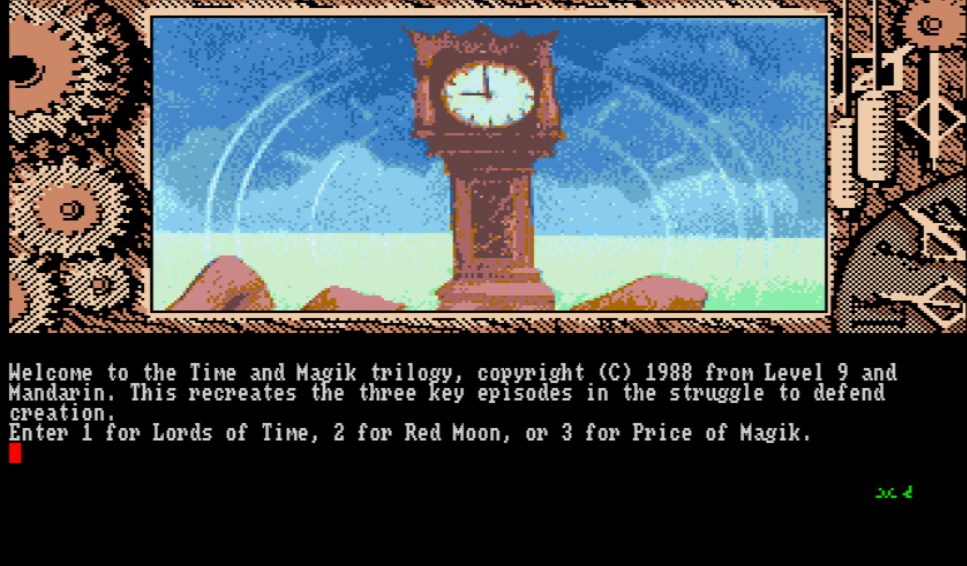

If "Timelords" sound familiar, it's not a coincidence. They were clearly inspired in part by the Time Lords of Doctor Who. Aside from the general time travel premise, the protagonist also goes to different time periods through a grandfather clock, not unlike the means of transportation used by the Doctor's frenemy, the Master. If this wasn't explicit enough, there's one point in the game where you're menaced by a Cyberman (also from Doctor Who), who you have to defeat with a lightsaber (not from Doctor Who, in case you needed the clarification).

Such references shouldn't be too surprising given that the game was written by Sue Gazzard, who was a British housewife. When her family got a BBC computer, she became enthralled with adventure games (sadly, the scraps of information on her I could find don't even hint at which games inspired her, although given the time and the apparent influences on Lords of Time I would be surprised if Zork wasn't one of them). She wrote the text and the puzzles for a game of her own and got in touch with Level 9, who decided to base their next game on her work, which was apparently the first time they commissioned someone out of house to design a game. Apparently some of her text was rewritten and a few puzzles were added. I couldn't find out how much her work was revised, but the sources I could find all suggest that Lords of Time was still very much her creation.

Her story, at least as much of it as I could piece together, is similar to that of Roberta Williams, who was also a housewife who became fascinated with adventure games and decided to try her hand at making her own games. Unfortunately, while Roberta Williams would go on to create a culture-shaping game series, King's Quest, and co-found a multi-million dollar company with her husband Ken, Sierra On-Line, Sue Gazzard would only be known for Lords of Time/Time & Magik. I found an unconfirmed claim that she did help develop two more games, but if she did, they were sadly never released.

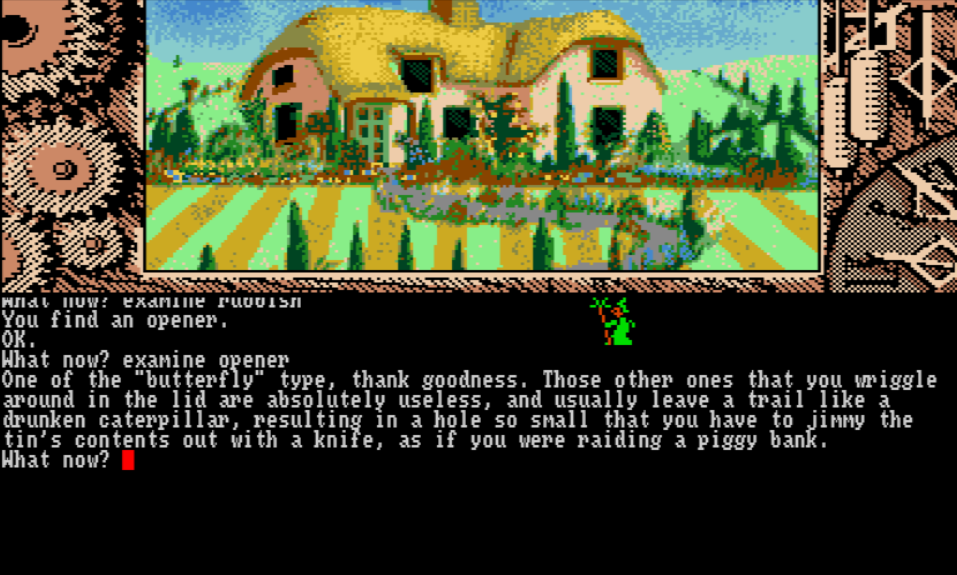

It is a shame, because there are two notable things about the text of Lords of Time: it's very detailed even by text-based adventure game standards, and it's very funny. Just look at how one item, a can-opener, is described if you examine it:

It's worth noting, too, that the unnamed protagonist of Lords of Time is a woman. This is something hinted at in a couple of points in the game if you pay close attention, but to me it becomes obvious once you solve one puzzle by kissing a frog and turning him into a handsome prince who will save you from getting killed by a knight. I know there were earlier female adventure game protagonists, but in 1984 it was still a rarity unless you were playing a game like Might & Magic that let you create your own characters.

Also, the game does drop references that went completely over my elementary school head. There's a reference to angel dust, for example.

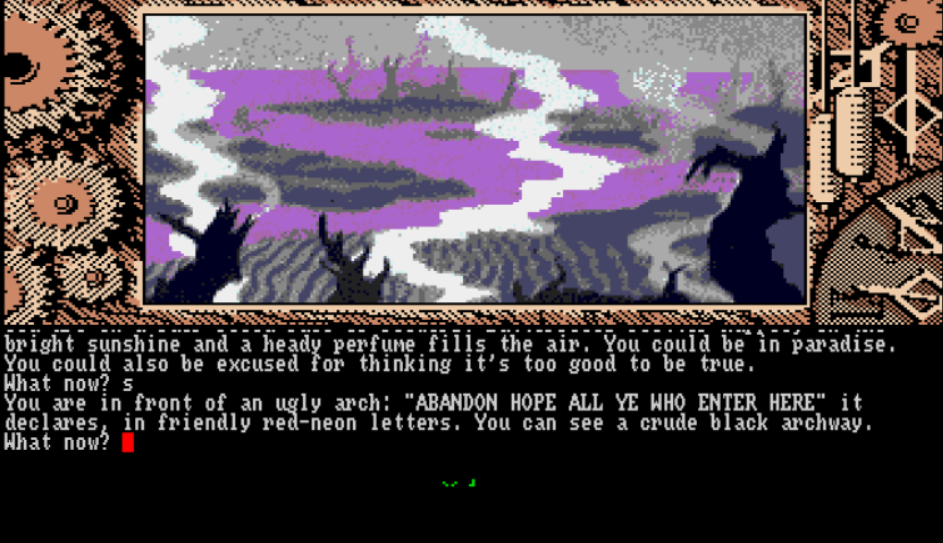

Speaking of my childhood self, I'm going to definitely be telling my age, but when I got Lords of Time, the family computer had nothing like Windows, just DOS, and the few games we had for it had primitive graphics with a color palette of just purples and greens and blues and whites. Still, I had never played anything quite like Time & Magik. The version of the game I had (which definitely was not the version I'm taking these screenshots from) only had one image at the beginning of the game, so it really was more like reading a novel, but one where I could interact with the world. I didn't have anything like it either on my computer or on my Nintendo. Before it, the only adventure game I had played was the Maniac Mansion port for the Nintendo, and that was definitely not heavy on text.

Honestly, I never made it far in either of the two other games included with Time & Magik, Red Moon and The Price of Magik. They weren't terrible games, far from it. In fact, they were rather experimental in how they tried even in a text-based game to combine RPG elements like turn-based combat with adventure game-style exploration and puzzles. But quirks of the gameplay, like the fact that enemies you defeated in combat could come back to attack you again as ghosts, frustrated me, and the writing in those games just didn't grip my attention the same way Time & Magik did. So I would just play Lords of Time over and over again, long after I had exhausted all the options available through the text parser, including the fact that every time you input curse words a lightning bolt would nearly strike you. It was to the point that following the rhythm of the game became comforting to me, like putting on a TV episode where you already know every line.

Part of the appeal was that it had a certain mystique that was beyond my understanding. Being a dumb, provincial kid in Amherst County, Virginia who had yet to discover Doctor Who and 1980s British sitcoms through PBS, I thought all the Britishisms in the game were just some strange, old-timey way of writing. That had to be why certain words were constantly spelled with "our" instead of "or", why one item is called a "rucksack" instead of a "backpack", and why the protagonist's inner monologue at one point exclaims, "Cor!"

I can't say the game is what steered me toward becoming an anglophile. But I can't say it didn't either.

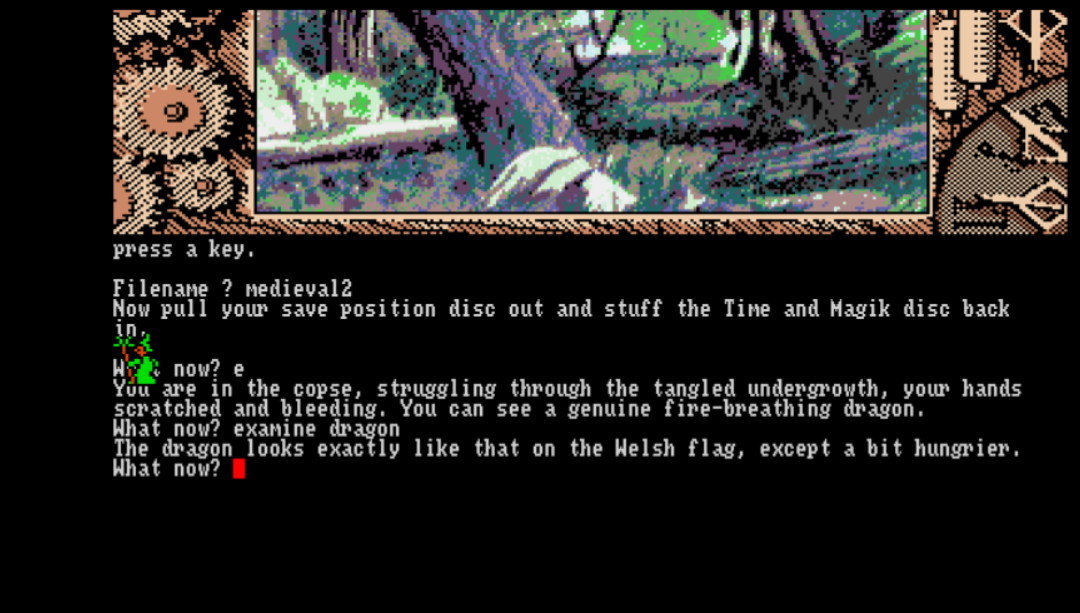

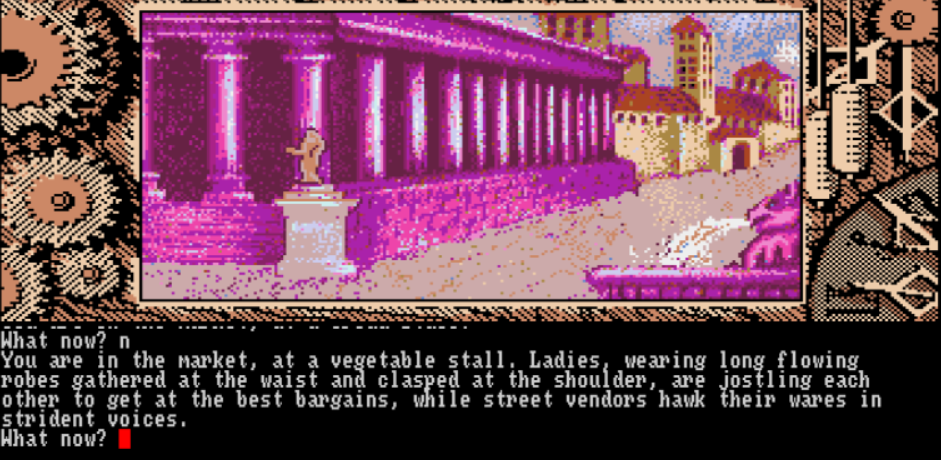

In preparation for this essay, I played through the Amiga version of the game, which had graphics, albeit in the form of several still images. Also I read a very lukewarm review by The Adventurers Guild. I can't disagree with many of their criticisms. Purely as a game, Lords of Time has some glaring flaws, I'll admit. There's errors in the programming; for example, there's a chance that if you drop an item you won't be able to pick it up again, even though the game will acknowledge that the item is still there. Some of the game's areas are underdeveloped (in fact, the ancient Rome portion of the game is so developed compared to the game's other temporal regions that I suspect Sue Gazzard is a woman who thinks about Rome as much as any man, to go by the Internet stereotypes of today). The difficulty of the puzzles is uneven, with only one puzzle requiring you to go back to an earlier time zone you already explored which could be a point of confusion since otherwise each of the game's nine time zones are self-contained. Also, like some other Level 9 games, the fact there's a limit on your inventory space is a nasty piece of artificial challenge, especially because, while you can come back later and pick up an item you discarded to make room for something else, it's also quite easy to make the game unwinnable by unwittingly discarding an item you thought you were done with and needed to access a certain area in that potentially unreachable area. It's even worse when you consider there's a considerable number of items in the game that are just "treasures" that add to your point total. Sometimes there's a hinted distinction between the items that are needed for puzzles and those that are just essentially trophies, but not always.

Oh, and then there's the hypocaust maze in ancient Rome. In it, you can only walk three screens before you have to drink water or die, and you only have one item that can provide water just once. I wouldn't hesitate to say that Lords of Time isn't as difficult or unfair as the notoriously ruthless adventure games Sierra became known for, but that one part of the game is downright sadistic. Even so, the game mitigates its own challenges a lot by including an option to "undo" the player's last actions.

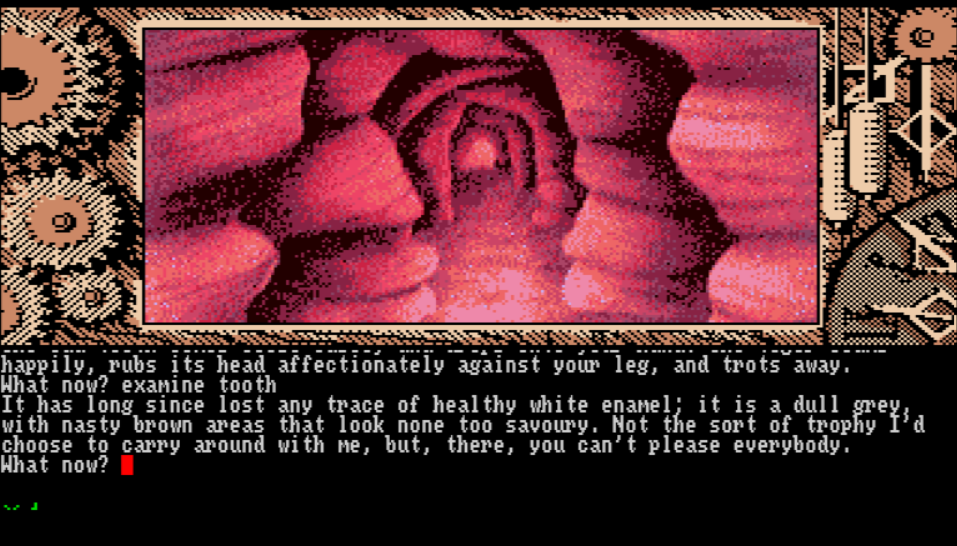

Depending on your point of view, the game might also be marred by the fact that it's unapologetically, aggressively silly. There are points where the game does strive for an authentic or frightening tone, like in the aforementioned ancient Rome area, but there's a point where you bargain with the Tooth Fairy, you ride a small dragon that ends up crashing in a moat and slinking away in embarrassment, a time zone with dinosaurs and cavepeople co-existing (although it's implied this is due to the Timelords' sabotage of the past), a literal fallen star that will talk to you like a fallen Hollywood star, and a surreal part where you're traveling on a walkway in outer space and climb something that's described as "the Milky Way." There's also a talking tree, although in that example the silliness is mixed with darkness, in that way the British do so well, once it turns out to solve the puzzle you help the tree commit suicide because it's deeply depressed by the nearby stream becoming badly polluted.

To be fair, though, this kind of tone was present in a lot of games of the time. Think of how the most powerful weapon in the early Wizardry games was the Cuisinart, named for a heavily advertised brand of food processor, or how Ultima II had "Hotel California" as a location you could visit.

Whatever the problems with the gameplay, I still genuinely enjoyed revisiting the game, even though at one point in my playthrough I managed to stumble into one of the aforementioned unwinnable conditions and had to go back to a much earlier saved game. The writing is rich yet crisp, especially if one takes the time to read item descriptions, and while there isn't much by way of plot or characters, especially by today's standards, the game itself has enough personality on its own. Even though I "cheated" by playing a slightly more upgraded version than the one I knew way back then, it did feel like visiting an old childhood friend. I even still remembered how to solve most of the puzzles, like muscle memory.

Revisiting this friend, I am also left in awe that it has such a place in my inner museum of nostalgia at all. A passion project by a British housewife somehow became a beloved, formative work of art in the life of a boy from rural Virginia, long before the Internet connected us all for better and (mostly) for worse.