Spooky Science and the Hope for a Weird World

It's time for me to come out of the closet. Not that closet, but the closet I share with people as diverse as Mike Stoklasa from Red Letter Media, Hidden Figures and Ma star Octavia Spencer, and the singer Jason Molina.

That's right, I believe in ghosts.

Of course, I dread the the eye-rolls from my more skeptically-minded friends enough that when I make this confession to them, I always have a trail of caveats and footnotes. Yes, I know Ed and Lorraine Warren were frauds (in fact, apart from one ghost tour guide who turned out to be a devout Christian, I've yet to meet or hear from a fellow paranormal believer who wouldn't agree); no, I don't usually watch ghost hunter shows or put any stock in them; no, I don't think most if any of the "professional" ghost detecting equipment you can pick up from sketchy websites do much of anything (although if you get enough drinks in me I'll sheepishly admit that I do own an EMF reader although at the time of this writing its exact location eludes me); and no, I haven't experienced anything myself that couldn't be rationally explained one way or the other. Also, I don't believe with confidence that ghosts are disembodied consciousnesses or emotionally-charged events imprinted on the fabric of space-time itself. Actually, I'm rather partial to both the hypothesis that ghosts are a kind of psychic debris cluttering up the collective consciousness and the Islamic concept of jinn, entitites who think and live much like humans but exist on another plane of reality and like to interact with us or at least screw around with us. I just think there is something substantial and mysterious to maybe 1-5% of all reputed tales of hauntings and ghost sightings, which may go beyond outright frauds or tricks of the human mind.

What especially interests me is the history of what I'll call for lack of a better word "ghost science" and its persistence in a world where I think skepticism or at least a kind of hard agnosticism on the subject has become the mainstream. A fascinating book on the subject is historian Deborah Blum's Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death. Blum's account follows the efforts of legitimate scientists in the Victorian era like William James to both debunk Spiritualist frauds while at the same time find empirical proof of the paranormal. Something that stands out is an interview I read (sadly, the link has been lost to the void of time) where Blum talks about how surprised she was that even present-day scientists and grad students in the hard sciences she spoke with had their own accounts of haunted labs and ghost sightings on college campuses. Except for people like Neil DeGrasse Tyson or James Randi whose first words in infancy were likely along the lines of "Um, please don't use the word 'spirit' around me even in a metaphorical sense", I think most of us have that itch that drives us want to find signs that there is more to the world than just flesh and decay, regardless of our own philosophical and religious orientation (or lack thereof). It's why science has never quite exorcised its spookier side. After all, the largest collection of papers related to the scientific study of reincarnation and past-life memories is still housed at the University of Virginia's Division of Perceptual Studies. As relatively recently as the 1970s and early 1980s, there was even a far-reaching fad for hard scientific investigations of the paranormal and psychic phenomena, which inspired movies like Ghostbusters and The Entity, the latter of which isn't as well-known but at least gave us one of the greatest examples of minimalist movie music of all time.

This leads me to my next claim, which if you're still reluctantly with me after saying "I believe in ghosts" might be the thing that finally drives you away (please subscribe anyway on your way out! I write about other things, I promise!). The current state of affairs with science and the paranormal wasn't inevitable. The course of the Enlightenment was shaped by philosophers like David Hume, who not only rejected the arguments for the existence of the soul, but wrote that such arguments are pointless because they cannot be proven through direct observation. Hume's point of view would come to dominate the Enlightenment and successive scientific movements, but perhaps in another world things went a slightly different way. After all, the Enlightenment produced both arch-empiricist David Hume and the Christian mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, the grandfather of many occult and New Age movements to come after his death. Perhaps we were just an intellectual movement or a successful book away from a present day where academic departments like the Division of Perceptual Studies are significantly more common and mainstream.

In any case, this brings me to the film I watched recently that inspired this little meditation of mine on hard science and the squishy topic of the paranormal, The Stone Tape from 1972.

More famous than the movie itself is its producer and writer, Nigel Kneale who also made several groundbreaking TV movies and series like 1968's Year of the Sex Olympics (which I promise to also write about sometime) and the Quartermass serials. He's also well-known for his outright abusive relationship with his fan, director John Carpenter. The Stone Tape was a huge influence on Carpenter's own movie about the intersection of science and the paranormal, Prince of Darkness, but Kneale bluntly admitted to Carpenter that he never saw the first two Halloween movies and had no intention of ever watching them. Still, Kneale was convinced to write a script for Halloween III, at the behest of several Hollywood names including Joe Dante who were all very much not John Carpenter. After producer Dino de Laurentiis in the usual fashion of shady Hollywood producers had Kneale's script butchered, however, Kneale demanded his name be removed from the film's credits. Never again would he even try to write for Hollywood.

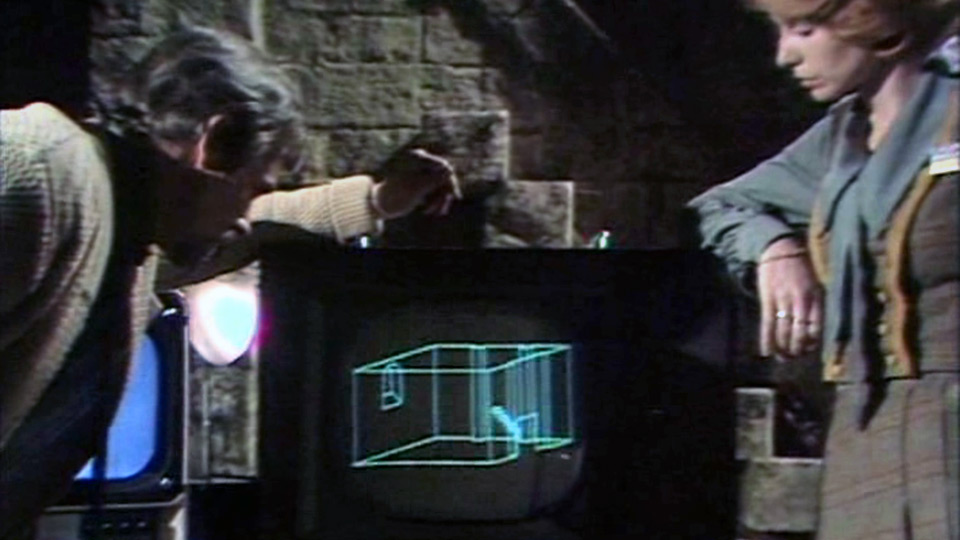

Luckily, though, The Stone Tape was a much more well-received production than the one Halloween movie famous for not having Michael Myers in it. It takes place, as you might expect from any British horror yarn, in an abandoned Victorian mansion. This time, however, the mansion has been purchased by a British corporation named Ryan Electronics, where they put one of their top researchers Peter and a team of computer scientists and engineers in hopes of coming up with products that will make Ryan Electronics competitive against the growing threat of the Japanese electronics market. However, Peter and his team quickly come up with convincing but not unambiguous proof that the ghost of a 19th century maid whose life was suddenly cut short inhabits the cellar of the mansion, which turns out to be far older than the mansion itself. The sole woman on his crew, a programmer named Jill, theorizes that the ghost is not so much an entity but an impression of a violent event preserved electromagnetically through the unique properties of the stone the cellar was built from, hence the term "stone tape." From this profound discovery, Peter can only gleam the idea that this evidence could form the basis of a new, revolutionary, and highly profitable type of audiovisual recording. This isn't enough for Jill, who becomes obsessed with the idea that there might still be other "recordings" on the stone tape, far older and far stranger than a screaming woman from the Victorian era...

The Stone Tape was originally envisioned as an episode of a horror-thriller anthology series, but the story was thought good enough for its own TV movie. And I can easily see why. My favorite horror stories tend to be ones where there's some explanation, but much is still left mysterious, and The Stone Tape hits that sweet spot. We have some explanation as to what's going on, but we never really learn what exactly has been inexorably connected to the cellar for nearly 7,000 years. Even if you can't get past the special effects (if you're familiar with Doctor Who from this period, you've got the idea of what they look like), at least the best horrors in this film are the subtle ones: the staircase in the cellar that seems to lead to nowhere, the anguished screams that only some of the people present can hear, and the panicked shout of "It's in the computer!", which is probably The Stone Tape's one contribution to the meme culture of today.

Like most good horror stories, there's also the more grounded elements. Of course, you don't have to be a zoomer to be uncomfortable at some of the resentment-fueled racism the characters show toward the Japanese, as much as it reflects genuine anxieties at the time The Stone Tape was made about Japan's possible economic and technological dominion. But besides a couple of awkward scenes, there is a grounded story of a female computer scientist who has to navigate her way through a work culture dominated by male co-workers, a scenario that unfortunately still resonates even five decades later. Also depressingly relatable is how a scientific discovery that shakes the foundations of what we think we know about reality is quickly turned into grist for corporate profit and how the short-sightedness of someone who ought to be a scientist ultimately not only ruins the potential of his discoveries, but costs actual human lives. Imagine what would happen if Elon Musk or Bill Gates stumbled across irrefutable evidence of the paranormal and what they would do with that information and you'd probably be surprisingly close to guessing the conclusion of The Stone Tape.

Like the movie it inspired, Prince of Darkness, The Stone Tape manages to be a better adaptation of H.P. Lovecraft than most direct adaptations of Lovecraft's stories. It starts as a ghost story, albeit an unconventional one, but ends on much the same note as Lovecraft's "Call of Cthulhu." I'm reminded especially of the fantastic passage that opens "Call of Cthuhu":

“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

Where The Stone Tape really succeeds in leaving its mark on the viewer is with the strange presence of what Jill terms "the others." Finding empirical evidence about the true nature of ghosts is just a first step. The rest of the path leads to places much more bizarre and dangerous and perhaps even beyond comprehension. And it's poor Jill, spurred on by the callous and soulless motives of Peter and Ryan Electronics, who has to pay the price of this knowledge.

All that said, I still wish science and technology were moving in the direction that writers like Lovecraft warned us about, instead of just producing boutique, algorithm-driven tech that isn't actually "Artificial Intelligence" and achieves little other than devaluing the work of artists and writers. Now that's where the true horror lies, at least for now.