Gender Panic

“Gender is a shell game. What is a man? Whatever a woman isn't. What is a woman? Whatever a man is not. Tap on it and it's hollow.”

-Naomi Alderman, The Power

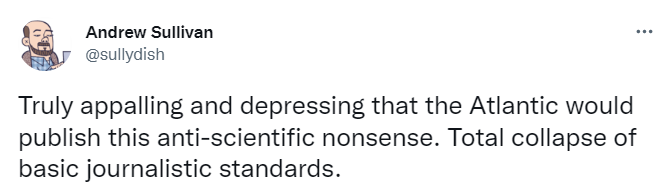

For a couple of days on Twitter, there was an apocalyptic buzz among the pundits. An article was published in The Atlantic, leading to demands for outright censorship among voices that are otherwise ready to decry what they deem “cancel culture.” Was the issue at hand the threat to democracy in the United States, rampant income inequality, or the rise in homelessness and suicide?

No, it was…gender segregation in school sports.

Now, to be clear, I’m not here to write about the offending article one way or the other. I’m a historian, not a biologist or an expert on athletics, and I’m really not equipped to argue the science of sex beyond my vague awareness of things like how recent research on chromosomes backs up the theory that biologically sex is a spectrum. Honestly, I was also much more interested in the apparently disproportionate reaction to Maggie Mertens’ essay than the work itself.

This outcry is not explicitly about trans identity and rights. Yet, it is impossible not to read such reactions in light of a moral panic that has involved factions ranging from “small government” conservatives pushing for the right to tightly regulate trans youth’s medical care and participation in sports to bomb threats being made against children’s hospitals. In the United Kingdom, it’s given rise to an entire movement, deeming itself “gender critical” or “Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists” (TERFs). It’s no exaggeration to say that their fixation on such anti-trans rhetoric cost Harry Potter creator J.K. Rowling some public good will and basically destroyed the career and even the personal life of Black Books and Father Ted writer Graham Linehan. But it’s not just a crusade for celebrities. Some pro-trans comments made by the First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, unleashed a flood of virulent responses. Glimpsing at the people disgruntled by Sturgeon’s comments reveals Twitter bios that are defined mostly or even entirely by their feelings about trans and gender issues. A few examples:

What fuels this fixation? Ironically, for even the ones claiming to come from a radically feminist, gender abolitionist stance, it’s about gender as much as it is for the most reactionary Christians. Gender is often if not always a social and political battlefield. This is something non-binary, trans, and lesbian and gay activists very well understand, even as reactionary and conservative voices scream that it’s their adversaries that are making gender an issue.

I’m not the sort of historian who believes economics drives every trend in history. But I do wonder how much of it is mixed with the social alienation and economic uncertainty that have been overshadowing the English-speaking world and beyond since even before the Great Recession of 2008. Certainly it feels like a deliberate distraction, how the media and politicians in the United Kingdom have been treating trans rights as a sort of existential, society-wide crisis at the same time energy bills have risen as high as 80%, and social services have crumbled to the degree that people are dying from a lack of emergency care. At the very least, trans and gender issues in both the United Kingdom and the United States have served as convenient rallying cries for center-right and far-right politicians who have nothing to offer but the usual recipe of slashing public spending, auctioning off infrastructure and public services to private interests, and stamping down on immigration. Unfortunately, as the world around them falls apart and as their children just don’t have the same opportunities they did, people tend to turn to whatever scapegoats are offered up to the altar.

Of course, none of this is entirely new. You could write a global history going back to ancient times about gender anxiety. Saint Augustine of Hippo was horrified by the mere existence of the cross-dressing gala priests who castrated themselves and dressed in women’s clothes and makeup for the impossibly ancient goddess Cybele. Centuries later, Christian missionaries and colonizers tried their best to eradicate any signs of cross-gender or “third and fourth” gender personas they found among the cultures they encountered in the Americas, Africa, and the Pacific. To this day, this history is often buried. In his pseudo-investigative documentary What Is A Woman?, theocratic provocateur Matt Walsh trumpeted how he found an African tribe that purportedly did not understand the concept of trans-ness. In fact, for just one example, the mudoko dako of modern-day Uganda were seen as women and were allowed to marry men. So, while you could debate whether or not such roles are in a historic continuity with modern trans identities (I’m inclined to think so, but that’s another discussion), gender roles are hardly something fixed and constant across time and geography. In a way, imposing Western ideas of gender and gender roles on foreign peoples was as much a tool of colonization as guns or puppet governments.

What I’m reminded most of is the Gender Revolution—not the one that unfolded in the 1960s, but the one that happened in the late 1700s. At the beginning of that century, gender roles in Europe were not quite so rigid. That’s not to say that women were free to lead armies or that men could dress completely as women, of course. Still, from France to Russia cross-dressing balls were all the rage, so much so we have a letter where Horace Walpole, a scholar, politician, and son of Britain’s first prime minister, wrote about finding a dress for a ball he would attend. In the late 1600s, writers like Mary Astell, François Poullain de la Barre, and Margaret Cavendish took inspiration from Descartes’ concept that the mind starts out as a blank slate and argued that gender isn’t something inborn, but something imposed through education and society.

As historian Gary Keates argued in Monsieur d’Eon is a Woman, this changed in the last decades of the eighteenth century. It's a development that can be traced in the change in fashion across Europe in the era. Men's fashions became more distinct, losing large wigs, lace, and frock coats that could sometimes resemble skirts. The popular and bestselling philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau was the main spokesman for this revolution, writing in his educational treatise Émile, "Women are wrong when complaining of the inequality of man-made laws. This inequality is not of man's making, or at any rate it is not the result of mere bias, but of reason. She who nature has entrusted the care of the children must hold herself responsible for them to their father.” Rousseau and other philosophical and medical writers of his time assumed that gender itself was embodied in the “nerves” of the body, an idea bolstered by the new anatomical discoveries of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This wasn’t an entirely new notion, nor did it completely displace the Cartesian idea of gender roles just being a matter of culture and education. However, in a Europe where life and knowledge itself was increasingly becoming regimented, gender roles being defined with the authority of reason had such an appeal many people came to believe it had always been so.

While gender has always been contested, I do think we are in the midst of another seismic transition in how gender is seen and lived. In not only the social sciences but in the wider culture, gender is becoming seen as something more fluid and more complex than simply entirely interior or socially performed. At the same time, there is a reactionary entrenchment that’s international in scope and whose full impact has not yet been seen, and whatever its causes, these bleak and precarious times can only draw people to it. It remains to be seen how this will all shake out, and, unfortunately, how much unnecessary pain and anxiety it will take to get to the other side.