Cameron Hodge, the X-Men's Moral Majority Foe

With the writers of X-Men ’97 doing a speedrun through some of the most memorable stories in the franchise, it was probably inevitable in the current climate that the debate over how “woke” the original comics are would creep up. Of course, the debate is already cast in bad faith terms by people more interested in clicks and views than in an actual discussion of art and social politics. Futile as it may be, though, it’s always fun to mix pop culture trivia with political arguments. Anyway, people in the “X-Men were always woke” camp usually mention how much being a mutant is an allegory for racial minorities and being LGBT (down to mutant powers usually manifesting in puberty) or how bluntly the Days of Future Past storyline is about the rise of fascism (albeit with sentient giant robots) and ethnic cleansing. However, I haven’t seen an article or a video essay mention my own preferred example of the X-Men getting political, which also happens to be one of my own favorite X-Men villains: the twisted life and career of Cameron Hodge.

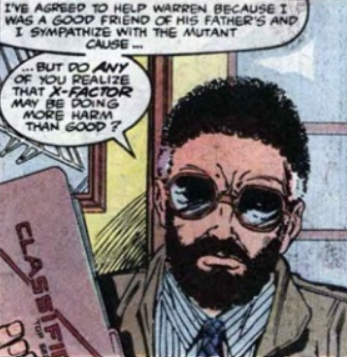

Although he was created by writer Bob Layton, Cameron Hodge really came into his own under the pen of Louise Simonson when she took over the X-Men spin-off, X-Factor, in 1986. To explain who he is and what he represents, though, we’re really going to have to take the express right into the core of X-Men continuity, so bear with me and don’t jump off the train just yet. At the time, X-Factor was a series for the original five members of the X-Men: Jean Grey, Cyclops, Beast, Iceman, and Angel. The premise was that, at a time of increasing anti-mutant hysteria, they would pose as a private business offering the services of “mutant hunters” while in actuality they would protect the mutants they were sent to capture and teach them how to control their powers. This was not even the former X-Men’s idea, but that of Angel’s close friend and college roommate, Cameron Hodge, who was a PR guru. If the premise sounds a little wobbly, well, that’s something that Layton himself explored within the text. It’s also worth nothing that, while X-Factor was born out of Layton’s genuine desire to bring back the old Silver Age X-Men team (sans Jean Grey, who was still dead at the time Layton made his pitch), it was also a by-product of several editorial mandates (such as resurrecting the aforementioned deceased Jean Grey) that made things awkward for all the writers involved.

I don’t believe it’s ever been disclosed what direction Layton wanted to go with the “ersatz mutant hunters” concept. But when Louise Simonson started writing X-Factor with issue #6, she started chiseling away to bring the whole premise crashing down. Ultimately, it turns out Cameron Hodge had been playing X-Factor like a harp from Hell, deliberately using the mutant hunters angle to stoke public anti-mutant sentiment while using Angel’s family wealth to help fund his own paramilitary organization, which is actually just named “the Right” (how’s that for woke?!).

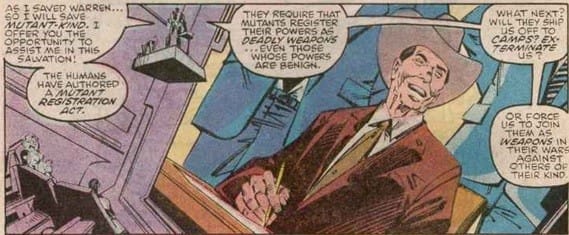

The real-world backdrop to Simonson’s X-Factor run was, of course, U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s administration and the rise of reactionary evangelical Christians as an organized national political force. These were understood even at the time as interconnected, as Reagan happily pandered to the likes of the evangelical firebrand Jerry Falwell and his “Moral Majority”. The pivotal 1982 X-Men epic, God Loves, Man Kills, even visually modeled its villain, Reverend William Stryker, after Reagan’s notorious Secretary of State, Alexander Haig, who had downplayed the murders of four American nuns and other human rights abuses under the military junta running San Salvador. In one issue of X-Factor, we see Reagan smiling while he signs the Mutant Registration Act. In X-Men lore, the Act was one of the key steps toward the dystopian future portrayed in Days of Future Past.

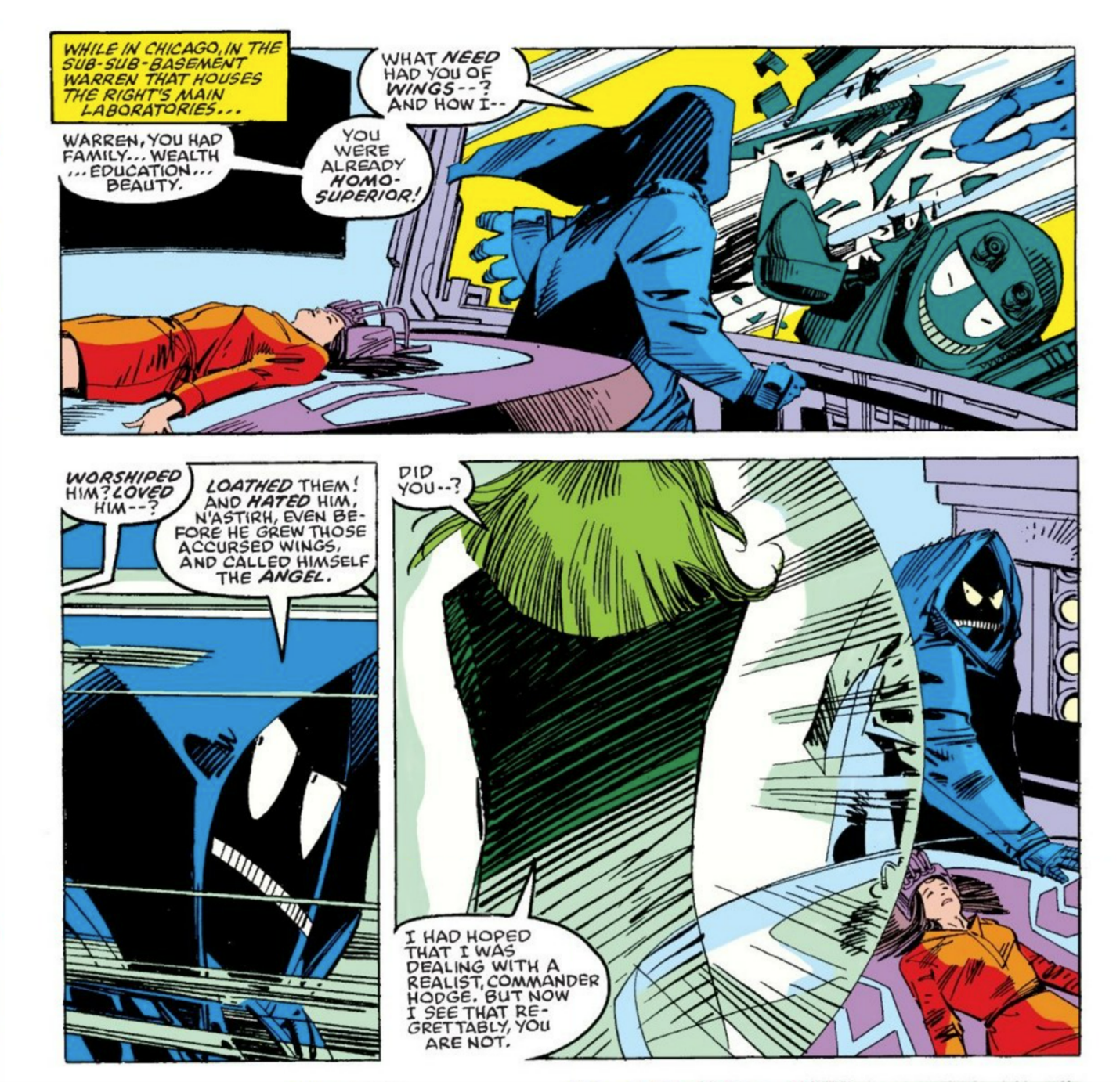

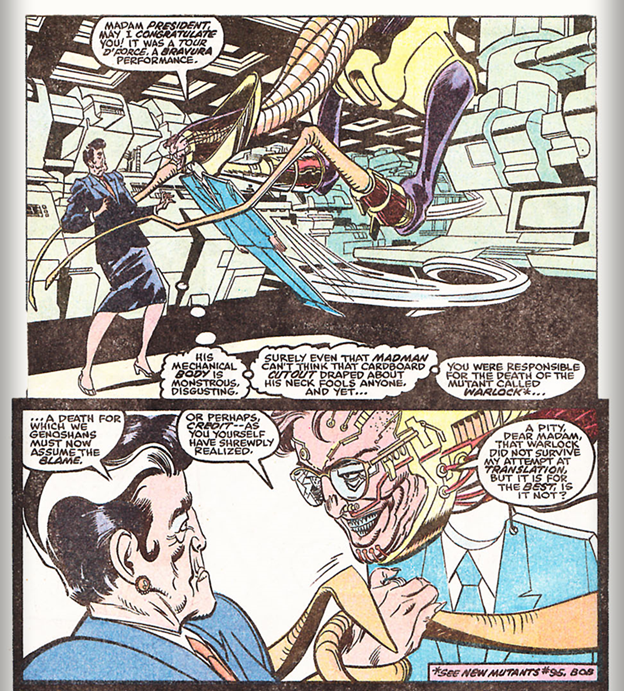

As Cameron Hodge’s ties to the Right and his own insanity are exposed to both the heroes and the reader, he gets presented as arguably the quintessential Moral Majority figure. Hodge is a respectable, successful businessman whose socially respectable veneer disguises a perpetually snarling bigot more than willing to countenance violence. More than that, though, Simonson spells out that Hodge’s motives aren’t simple and pure. In fact, they’re quite personal. There’s this exchange between Hodge, wearing the delightfully bizarre uniforms of the Right, and the demon N’astirh:

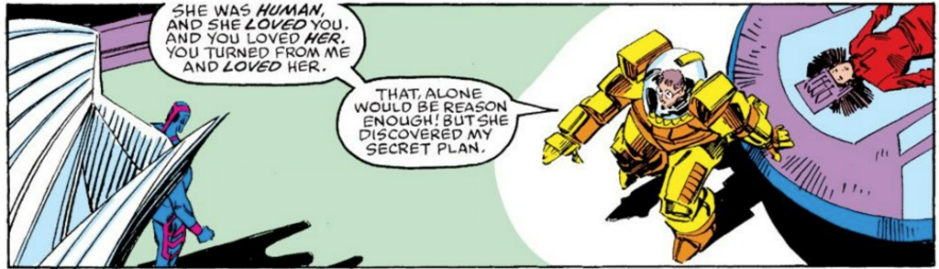

In case that wasn’t clear enough, here’s Angel (now transformed into “Archangel” as a result of another X-Factor storyline) confronting Hodge, who has killed Archangel’s love interest, Candy Southern:

The Reagan era was a low point for the struggle for gay rights. States had been gradually decriminalizing sex between partners of the same sex over the course of the late 1960s and 1970s, and even in the conservative Reagan era Wisconsin followed suit in 1983. However, the Reagan administration catastrophically ignored the spread of HIV/AIDS and American conservatives promoted the idea that it was a disease that only concerned (and was morally deserved by) gay men. Reagan and his supporters also encouraged a cultural backlash against even mildly positive portrayals of homosexuality in media (Matt Baume did an excellent video on one such front in this culture war, involving an openly gay character on the comedy Soap). Marvel Comics itself had succumbed to the backlash, thanks to its then editor-in-chief Jim Shooter who reportedly banned all gay and bisexual characters. The edict forced Alpha Flight character Northstar into the closet until 1992, more than a decade after the character’s creator, John Byrne, first intended for Northstar to be written as an openly gay man. Naturally, writers got around the ban, perhaps most famously with Chris Claremont in X-Men all but explicitly writing the characters Mystique and Destiny as a same-sex couple that lived together and raised the X-Man Rogue as their adopted daughter (later, it came out that Claremont originally also intended for the X-Man Nightcrawler to be their biological son, conceived when Mystique used her shapeshifting powers to impregnate Destiny, an idea that only recently became canon). There were several others, though, like Arnie Roth, a childhood friend of Captain America. In one story, Captain America helped Arnie rescue his male “roommate.”

Of course, maybe Shooter would have been fine with an obvious villain being warped by their same-sex desires. Such implications are why nowadays people tend to frown upon the trope that homophobes are themselves frustrated, self-hating gay people. That said, though, I would argue that Cameron Hodge is a provocative antagonist then and now. The idea that his anti-mutant fanaticism is rooted in his own suppressed sexual and romantic frustration is an interesting and valid take on the psychology of hatred, even today. Even past his real motivations, Simonson’s Hodge is just such a riveting and convincing interpretation of the reactionary mind. His public persona is a hollow shell, his principles are all-consuming and yet amount to only a justification for his own grievances. His claims of righteousness are undercut by a willingness to bargain with demons (in the case of Hodge and the demon N’astirh, literally!). And, while he takes obsessive pride in his “pure” humanity, his appearance only becomes more grotesque and monstrous as a consequence of his own actions.

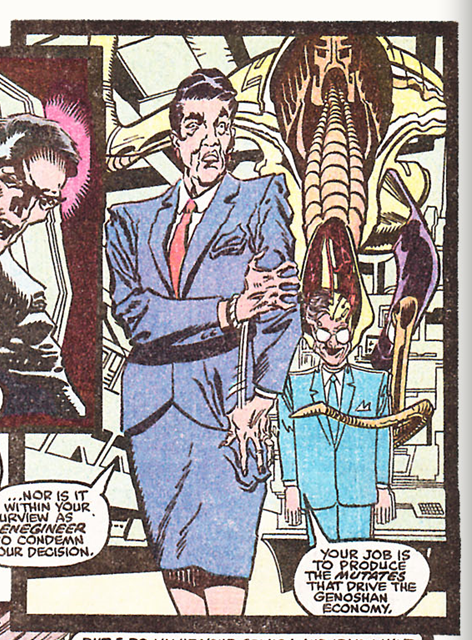

See, N’astirh bequeathed Hodge with immortality. Unfortunately, as a former PR expert, Hodge should have known that he ought to have put some clauses in the deal. Enraged by Candy’s murder, Archangel decapitated Hodge with his metallic wings. Because of the deal with N’astirh, Hodge’s head still survived, just without a body attached. The Right then attached Hodge’s head to a bizarre insect-like robot (given how badly being a living head without a body affected Hodge’s already questionable mental health, I suspect it was Hodge’s choice). Despite that, Hodge managed to pick up a new gig, working for the government of the island nation of Genosha, whose booming economy was built on the backs of enslaved and genetically modified mutants. He only just barely clings to a shred of his old respectable humanity by draping a cardboard cutout of a body in a business suit around his neck.

And yes, the artist Jon Bogdanove in X-Factor depicts the female president of Genosha as strongly resembling Ronald Reagan. Nor can I resist pointing out the political commentary inherent in having the ruler of a modern-day slave state be from a marginalized group themselves. I know there’s no point in arguing about “wokeness” in X-Men before whatever arbitrary point in time is in question, but come on…

Since that storyline, the X-Tinction Agenda of 1990, Cameron Hodge has reared his immortal head. Most notably, he was an ally/pawn of the techno-aliens, the Phalanx. But often he just appears in team-ups with the X-Men’s other militantly human enemies. Personally, though, I would like to see him once again take a prominent place among the X-Men’s rogues’ gallery. After all, the fundamental metaphor of a zealot who devolves from being an upright member of society into something truly and visibly monstrous is still depressingly relevant.